The social justice views of Supreme Court nominee Sonia Sotomayor have deep roots.

Several recent articles in both liberal-progressive and conservative media attributed Judge Sonia Sotomayor’s interpretation of the law to the doctrine of legal realism. Specifically mentioned in that connection was 1920s and 30s legal scholar Jerome Frank.

In fact, Mr. Frank was just one voice, although a prominent one, among many legal scholars who articulated the doctrine of legal realism. That doctrine’s genesis goes back to Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr.’s 1881 lectures at Harvard law School, later published as The Common Law. Holmes in 1902 was elevated to the Supreme Court by President Theodore Roosevelt, a Harvard graduate and early member of the Eastern liberal-progressive establishment.

Holmes’s The Common Law was an attack on the validity of the common law, on which English and and then American jurisprudence had heavily relied since the 12th century. The thrust of his lectures was a call to reform much of the common law to reflect current experience. Such reform, however, would have to come from judges’ reinterpretation of hitherto settled principles of law.

While there was validity in his questioning modern applicability of legal procedure rules that had originated in ancient Germanic tribal custom and in early Anglo-Saxon practice, Holmes’s argument opened the door to judicial activism. The Common Law influenced a generation of lawyers to reject one of the most fundamental precepts underpinning the Constitution: the idea that the courts were to be neutral interpreters of the Constitution and legislative enactments.

Returning to Jerome Frank, the aforementioned influence on Judge Sotomayor, what was his view of legal realism?

In Law and the Modern Mind (1930), Mr. Frank starts from the truism that clients, and lawyers equally, want to have as much certainty as possible about predicting what a judge will decide in a specific case. Clients and lawyers, in effect, want to know what is the law respecting specific cases.

The problem, in Mr. Frank’s analysis, lies in interpretation of facts. He writes that, “.particularly when pivotal testimony at the trial is oral and conflicting, as it is in most lawsuits, the trial court’s “finding” of the facts involves a multitude of elusive factors.” It is thus often “impossible, because of the elusiveness of the facts on which decisions turn, to predict future decisions in most (not all) law suits, not yet begun or not yet tried.”

Every judge, he says, has some degree of prejudice or preference, often in ways the judge is not aware of. Those prejudices or preferences will influence the way a judge interprets facts in specific cases, which in turn points the judge to one of various possible interpretations of the law.

In this 1930s assessment, we see a foreshadowing of Judge Sotomayor’s 2001 Cal-Berkeley lecture statement that “.a wise Latina woman… would more often than not reach a better conclusion [as a judge] than a white male.” The implication is that a wise Latina judge would be more inclined by her social and economic heritage to interpret the facts of a case in ways that would lead to a decision conforming to liberal-progressivism’s understanding of social justice. Legal realists see their mission as undoing centuries of legal doctrine that supported the rights, particularly the Fifth Amendment guarantee of private property rights, which militated against the entitlements of blacks, Hispanics, women, homosexuals, and other special interest groups.

It is only fair, however, to acknowledge that Mr. Frank’s assessment of inescapable judicial prejudices applies to all judges, conservative or liberal-progressive. In the 1930s, when Mr. Frank wrote his book, it was liberal-progressives who complained that conservative judges were practicing judicial activism when they ruled against social justice legislation enacted in liberal bastions like New York State.

Mr. Frank points out that there is no single school of legal realism. It is a creation of legal theorists in Ivy League law schools as an outgrowth of socialist doctrines of social justice adopted by the Eastern liberal establishment early in the 20th century.

Mr. Frank writes, “Actually, these so-called realists have but one common bond, a negative characteristic already noted: skepticism as to some of the conventional legal theories, a skepticism stimulated by a zeal to reform, in the interests of justice, some courthouse ways.”

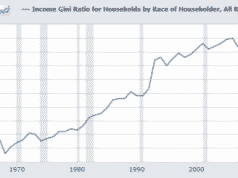

For Mr. Frank, and for most legal realists, justice seems to mean, not what the law says, but the social justice of socialism, i.e., affirmative action and redistribution of income and wealth, driving everyone down to a common economic level, without regard to individual intelligence, ability, productiveness, or hard work.

Legal realism is a species of power politics, the “might makes right” view that those wielding judicial authority are entitled to, and ought to, interpret the law in whatever ways are needed to produce economic and social equality. Under legal realism, the courts become a sort of super-legislature empowered to write their own versions of law, in defiance of the Constitutional rights of states, Congress, and the Presidency.

As Thomas Jefferson bitterly noted in his objection to Chief Justice John Marshal’s assertion of the Supreme Court’s right to declare executive action and legislative enactment unconstitutional (Marbury v. Madison, 1803), that presumption of power makes the Supreme Court, not a co-equal with the other two branches of government, but the final authority over the entirety of government. This was, in the eyes of those who fought for independence in 1776 and wrote the Constitution in 1787, a gross distortion of the Constitution amounting to tyranny.

The impetus behind Mr. Frank’s conception of legal realism and that of other Ivy League theorists is the great economic change after our 1860s Civil War, when industrialization first appeared on a vast, interstate scale, accompanied by the immigration of roughly 20 million poor laborers from eastern and southern Europe. Christian churches’ concern for the welfare and health of these laborers, who usually lived in terrible conditions in city slums, led to the Social Gospel movement and thence to the belief among academic materialists that pure socialism would be the best way to deal with the social problem.

Buttressing the legal realism view that the law is no more than whatever a judge declares it to be was the philosophical doctrine taught by John Dewey at Columbia University in the early decades of the 20th century.

Dewey’s conception was that Darwin had proved all things to be continually in evolutionary flux. If so, he opined, there can be no such thing as timeless moral principles. Morality in his view is no more than changing public opinion, which is another way of describing moral relativism. Justice Homes, in that regard, wrote that judges should not stand in the way if majority public opinion demanded replacing the Constitution with bolshevism.

Obviously, if there is no permanence to morality or the law, then judges are within their rights to impose their conceptions of what the law ought to be, provided public opinion supports their rulings.

The Legal Encyclopedia states:

In “The Nature of the Judicial Process,” a groundbreaking book first published in 1921, [Supreme Court Justice] Cardozo argued that law is a malleable instrument that allows judges to mold amorphous words like reasonable care, unreasonable restraint of trade, and due process to justify any outcome they desire.

Convinced that common-law principles can be manipulated by the judiciary, Cardozo was concerned that instability and chaos would result if every judge followed his or her own political convictions when deciding a case. To forestall the onset of such legal disarray, Cardozo and other realists argued that all judges must interpret the law to advance the welfare of society. “Law ought to be guided by consideration of the effects [it will have] on social welfare.”

Legal realism, however, is many leagues removed from the understanding of law and the role of courts at the time the Constitution was written.

Alexander Hamilton wrote in Federalist No. 81:

The arguments, or rather suggestions, upon which this charge [objections to the powers accorded the Federal judiciary by the Constitution] is founded, are to this effect: “The authority of the proposed Supreme Court of the United States, which is to be a separate and independent body, will be superior to that of the legislature. The power of construing the laws according to the SPIRIT of the Constitution, will enable that court to mould them into whatever shape it may think proper; especially as its decisions will not be in any manner subject to the revision or correction of the legislative body. …

In the first place, there is not a syllable in the plan under consideration which DIRECTLY empowers the national courts to construe the laws according to the spirit of the Constitution, or which gives them any greater latitude in this respect than may be claimed by the courts of every State. I admit, however, that the Constitution ought to be the standard of construction for the laws, and that wherever there is an evident opposition, the laws ought to give place to the Constitution. But this doctrine is not deducible from any circumstance peculiar to the plan of the convention, but from the general theory of a limited Constitution.

Thomas E. Brewton is a staff writer for the New Media Alliance, Inc. The New Media Alliance is a non-profit (501c3) national coalition of writers, journalists and grass-roots media outlets.

https://thomasbrewton.com/

Email comments to viewfrom1776@thomasbrewton.com