It has become a tired cliché. Battling climate change is analogous to fighting a war. Al Gore, Prince Charles, filmmaker James Cameron – even educators and marketers – employ this rhetoric. Once we begin thinking in such terms, it may be a short step to believing that wartime measures such as energy rationing are necessary.

In 2006, UK environmentalist Mark Lynas authored a column for the New Statesman. It contained declarations such as:

The best indication of whether a person truly grasps the scale of the global climate crisis is.whether they support carbon rationing.only a top-down carbon rationing scheme can deliver a predetermined outcome with any certainty.

For individuals, carbon rationing would operate as a parallel currency: when purchasing high-carbon goods (petrol for a car, overseas flights) a proportion of carbon currency would be surrendered at the point of sale. if you’re buying bananas or having a haircut, the carbon ration will already have been paid for by the company, and its cost built into the end price for the consumer.

In other words, a world in which CO2 emissions are rationed is a world in which we pay twice (in two currencies rather than one) – and pay more.

Lynas thinks the people who attend his speeches support rationing. Yet in the next paragraph he admits the public can’t be permitted to make up its own mind:

whenever I propose carbon rationing at public meetings around the country, it seems to generate a spontaneous round of applause. Perhaps the public is less backward on climate change than many politicians like to assume.

imposing such a scheme – and imposed it must be, as participation could not be voluntary – would require political leadership.

According to Lynas, state coercion in this regard wouldn’t be

incompatible with democracy. Who would march in Trafalgar Square against solving climate change? Probably about as many people as marched against rationing in 1940: none.

Considering that real bombs were then being dropped on Britain, it’s perhaps understandable that people had other priorities. But that war was different from the one Lynas believes he’s fighting. Many of us see the climate change campaign as a senseless battle against hypothetical bad things that might or might not happen at some distant point in the future. We are far from convinced there’s a genuine planetary emergency. Moreover, even those who believe in this emergency may think alternative responses (such as a massive expansion of nuclear power) should be undertaken first.

Technology has advanced considerably since the 1940s, so the consumer experience of rationing would no doubt be improved. But let there be no confusion: wartime rationing spawned its own set of problems. For one thing, it nourished the black market and, by extension, organized crime. People in every walk of life – consumers, shopkeepers, farmers, speculators, hoarders – had powerful incentives to game the system, to find small and large ways to cheat.

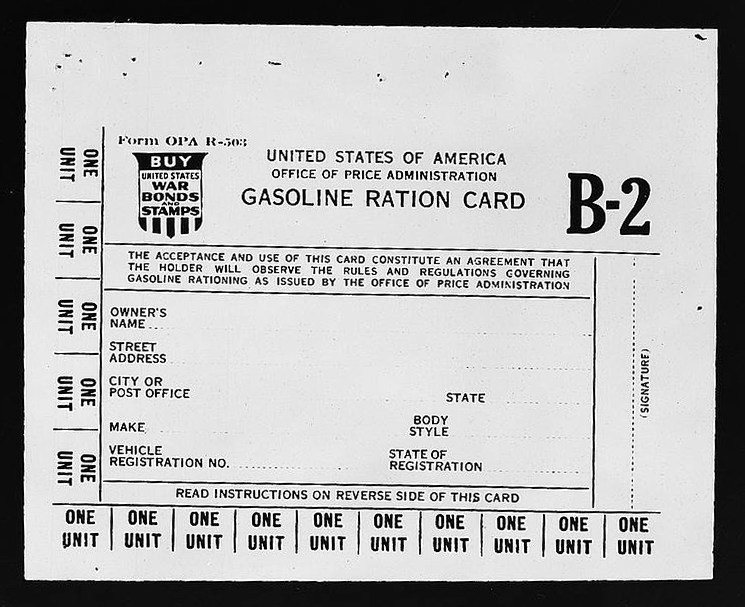

An Oregon State Archives discussion of rationing during World War II – titled Rationing: A Necessary But Hated Sacrifice – is well worth a read. In the US, the government body responsible for rationing “set up complicated rules” and was “everyone’s favorite wartime scapegoat.” Consumers grumbled as they lined up for their ration books and then lined up again to make purchases. Rationing was “replete with red tape, including coupons, certificates, stamps, stickers, and a changing point system.” Here’s the part about wartime gas rationing:

The elaborate system of gasoline rationing caused more headaches for consumers. Each driver was assigned a windshield sticker with a letter of priority ranging from A to E. Cars used only for pleasure driving wore an A sticker worth one stamp redeemable for three to five gallons a week.Commuters were assigned B stickers worth a varying amount of gas depending on their distance from work. E stickerholders received as many gallons as needed but this designation was reserved for policemen, clergymen, and similar professions. Farmers were also granted as much gas as needed but faced a daunting amount of paperwork to claim it.

New laws, new kinds of crime, and new law enforcement challenges were part of the mix. Private individuals who bent the rules in order to, say, acquire a special cut of meat to celebrate an important occasion were accused by government bureaucrats of being “secretly in sympathy with Hitler or Hirohito.” Members of the public were also encouraged to report to the authorities any rationing violations committed by their fellow citizens.

Which part of the above lifestyle sounds appealing? Is there anyone naive enough to imagine that a political party that introduced this sort of ‘hated sacrifice’ in the name of fighting climate change would have the slightest hope of being re-elected?

Photos from the American Memory Collection. Ration card info here. The label accompanying this image reads: “Gasoline ration card B2. This card is issued to the owner of a registered vehicle who has satisfied the rationing authorities that his vocational requirements are not properly met by the basic card A, and also exceed those provided by the card B1. The Registrar determines an applicant’s right to the B1, B2 and B3 cards on the basis of the facts set forth in the application.”

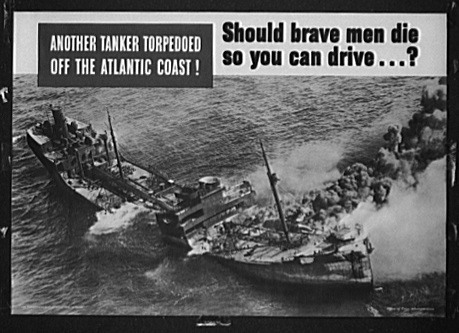

Poster info here. This label reads, in part: “Gasoline rationing poster. Poster distributed to gasoline stations and garages to educate motorists on need for fuel rationing.”